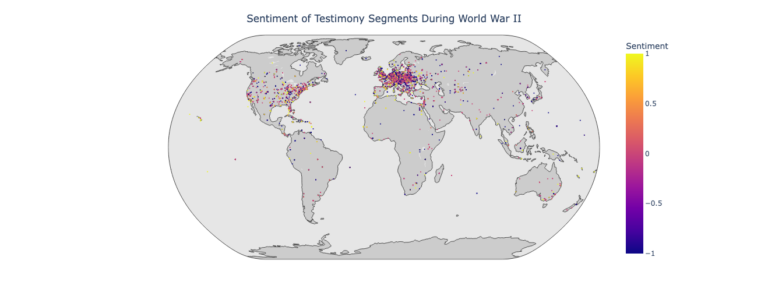

Geographies of Affect–Place and Sentiment in Holocaust Testimonies

Contemporary sentiment analysis tools lack the level of nuance and dedication to detailed description that Boder exhibited. Sentiment analysis tools are limited in multiple dimensions, including inabilities or ineffective accounts for tone, sarcasm, negations, comparatives, and multilingual data, and these weaknesses are enhanced especially when applied to complex texts in digital humanities. For this capstone project we tested different implementations of sentiment analysis to compare their affordances and limitations. I compared GPT-3 with GPT-2 and GPT-2 Fine tuned. I then mapped the results to visualize the geographic distribution of sentiment before during and after World War II.Read More

Advanced Googling It

I this online workshop I introduced artists, academics and activist to tools for finding digital resources and scraping data for research purposes.Read More

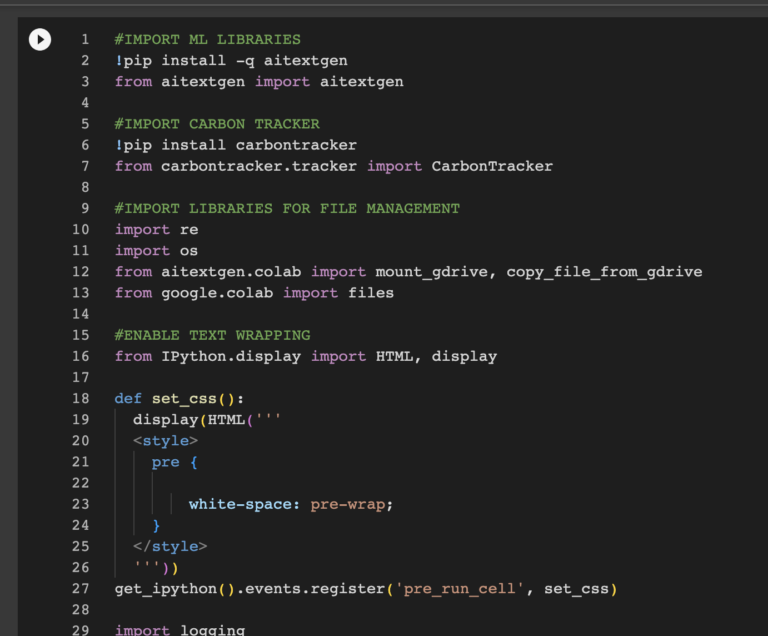

Introduction to Text Generation with Large Language Models

In this short course on text generation with large language models I introduce students to the basic concepts surrounding transformer models and how they differ from previous approaches to language generation. I also introduce students to concerns surrounding training data, biases, and the energy costs of training large models. In the hands on component of the workshop, I guide students through a python notebook that introduces them to concepts such as prompt engineering, fine turning and methods for studying biases in text generation output. The notebook is structured in a way as to not require knowledge of python to complete, while still giving students a deeper understanding of how text generation models work. Read More

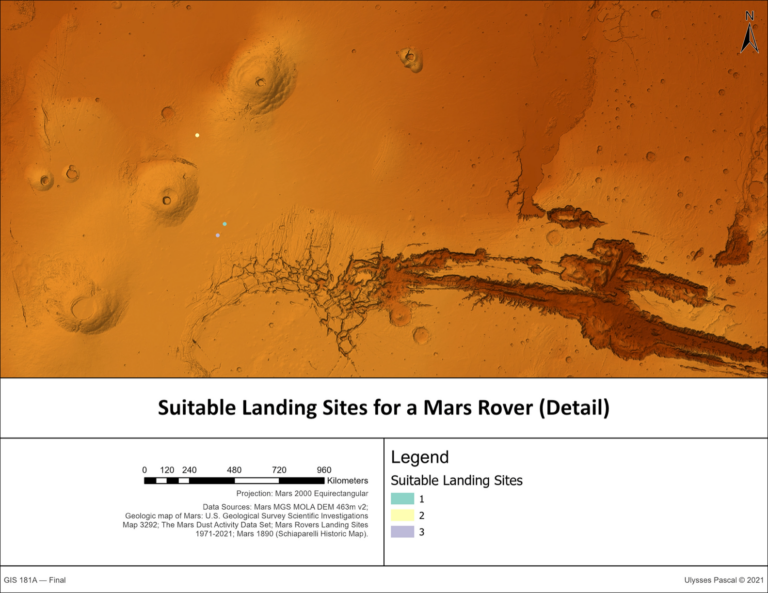

Revisiting Schiaparelli’s Martian Canale

For Geography 181A (Intermediate GIS) I conducted an analysis of Giovanni Schiaparelli’s historic maps of Martian Canale. In this speculative project, Georectified Schiaparelli’s historic maps and combined them with contemporary remote sensing data regarding conditions on the Martian surface to identify suitable landing sites to study Schiaparelli’s Canale. Read More

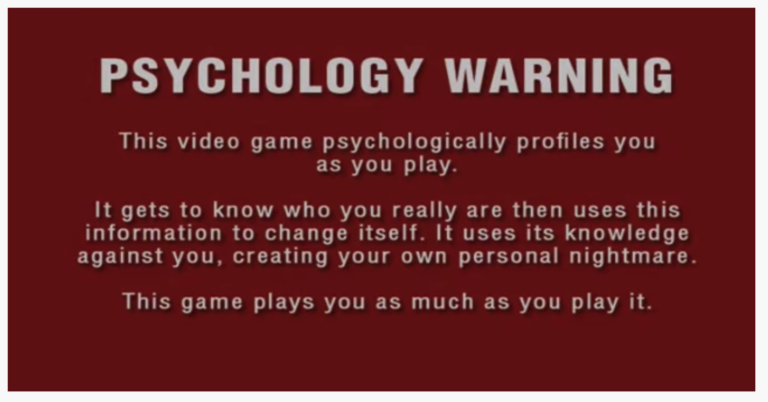

The Gamification of Games

Despite its name, gamification has never really been about making experiences more game-like. If there were a common characteristic that defined all games, it would certainly not be the use of badges, achievements, and points as incentives for engagement. Games, if anything, share an embodiment of the spirit of play — a temporary suspension of the rules of life to make space for intensities of experience: levity, rivalry, concentration, joy. If historian Johan Huizinga — whose 1938 book Homo Ludens is one of the pivotal works of game studies — had the opportunity to define gamification according to his theory of play, he might have reserved the term for a “temporary abolition of the ordinary world” where “inside the circle of the game the laws and customs of ordinary life no longer count.”

Now gamification evangelists like Jane McGonigal advocate for games to be understood as fundamentally productive, offering a set of tactics to make life under neoliberalism appear more fun and addictive — a “magic circle” we should never step out from, even if we had the choice. The concept first gained traction at the end of the 2000s within game development and marketing communities, which saw an opportunity to use aspects of games to monetize the web. In 2008, before the word had a standardized spelling, a blog explained “gameification” as “taking game mechanics and applying [them] to other web properties to increase engagement.” In the Wharton School of Business’s popular online course titled Gamification, the instructor professes that “there are some game elements that are more common than others and that are more influential than others in shaping typical examples of gamification.” These elements are “points, badges, and leaderboards.” These offer scores that constitute “a universal currency, if you will, that allows us to create a system where doing one sort of action, going off on a quest with your friends, is somehow equivalent or comparable to doing some other sort of action, sitting and watching a video on the site.”

For the my full article on the gamification of games see: https://reallifemag.com/the-gamification-of-games/